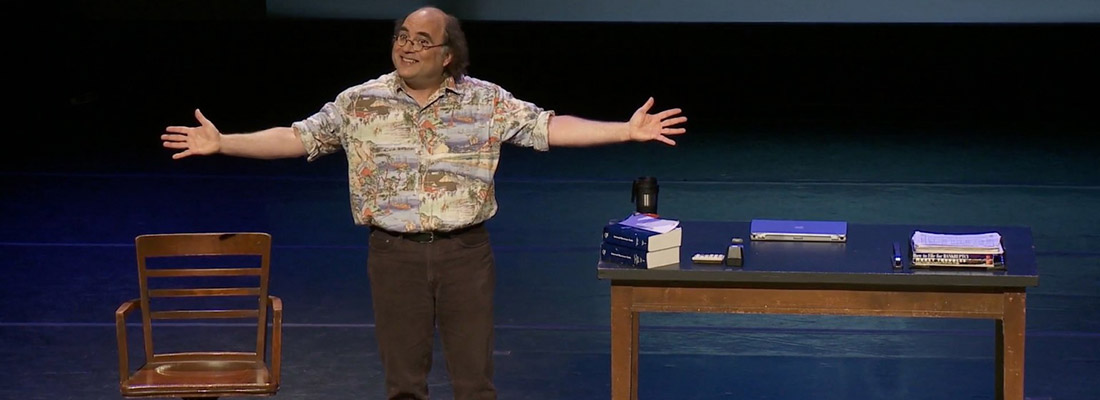

Much of my creative focus for the next several months will be on expanding Andy Warhol: Good for the Jews? — an hour-long presentation I did in January, commissioned by the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco — into a full-length theatrical monologue, which will debut at Theater J in Washington D.C. in March and then play at the Jewish Theatre San Francisco in April and May. My director and producer, as they have been (thank heaven) for years, are David Dower and Jonathan Reinis, respectively; I am also working with two of my favorite collaborators, designer Alex Nichols and composer Marco d’Ambrosio.

Much of my creative focus for the next several months will be on expanding Andy Warhol: Good for the Jews? — an hour-long presentation I did in January, commissioned by the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco — into a full-length theatrical monologue, which will debut at Theater J in Washington D.C. in March and then play at the Jewish Theatre San Francisco in April and May. My director and producer, as they have been (thank heaven) for years, are David Dower and Jonathan Reinis, respectively; I am also working with two of my favorite collaborators, designer Alex Nichols and composer Marco d’Ambrosio.

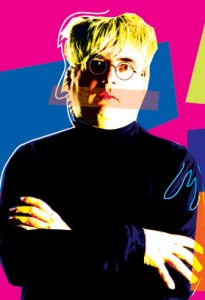

The original challenge laid down by the CJM’s commission was fairly simple: I was to visit (and, as it turns out, revisit and revisit) their exhibition “Warhol’s Jews: Ten Portraits Reconsidered,” guest-curated by Prof. Richard Meyer of USC. The 10 portraits at the center of this exhibit were of famous 20th-century Jews whom Andy Warhol — after what turns out to have been a quite interesting and collaborative process of selection — had committed to silkscreen in 1980. The collection (which appeared at the Jewish Museum in New York, among many other places) was received at the time with commercial euphoria and, for the most part, critical vituperation. Hilton Kramer’s 1980 New York Times review is one of the nastiest I have ever read. Here’s how it begins (as quoted in Meyer’s terrific essay in the recent show’s catalogue):

To the many afflictions suffered by the Jewish people in the course of their long history, the new Andy Warhol show at the Jewish Museum cannot be said to make a significant addition. True, the show is vulgar. It reeks of commercialism, and its contribution to art is nil. The way it exploits its Jewish subjects without showing the slightest grasp of their significance is offensive — or would be, anyway, if the artist had not already treated so many non-Jewish subjects in the same tawdry manner. No, the Jews will survive this caper unscathed. So, very likely, will everyone else. But what it may do to the reputation of the Jewish Museum is, as they say, something else.

Wow — tell us what you really think, Hilton!

I knew nothing of Warhol — and, sad to say, not so much about my fellow Jews (other than what I had picked up via osmosis by hanging out in various delis) — when I began working on this project. Since then, I have been trying to make up for lost time — chatting up rabbis (well, two), reading books and articles on Warhol and Jews, and listening to audiobooks and watching videos by and about Warhol and about Jewish history. For a Jew raised about as secularly as possible — and by parents who were no fans of Pop Art, either — this process is a great challenge, both exhilarating and confusing.

In a phone conversation I had with David today (he’s in Washington D.C.; I’m in Portland, Ore., right now), he pointed out that my previous monologues have placed me in various roles — son, husband, father — but have perhaps not actually come to terms with who I am (other than in relation to others). I find this idea to be quite provocative, and will try to pursue it as I continue my researches and improvisations (assuming, of course, that there is an “I” to do the investigating). A question that also interests both of us is how much of my parents’ communism may have been derived from the Jewish traditions that they broke away from. (In my mom’s case, the rift actually came a generation earlier.)

Hovering over all the proceedings — as I study the Jews, as well as the very religious (Catholic) Warhol — is my continuing lack of belief in God (at least, as some sort of supernatural being), which is somehow joined with my lifelong fascination with theology. (When you’re a Jewish atheist who spends six formative years at an Episcopalian choir school and has a communist father who’s obsessed with Jesus, some weird things can happen, I guess.)

In any case, there’s a lot to chew on here — and as I gnaw away at this juicy material, I will try to share elements of the process in this blog. Anyone who is interested is invited — nay, beseeched — to join in the process in the “comments” section beneath each entry. If there’s one thing I already know, it’s that dialogue is good — and not only for the Jews!

Actually, Josh, I think the previous monologues really only deal with two roles: Son (all the way through Franklin) and then Father (Taxes and Citizen Josh). Which leaves the space of who the character “Josh Kornbluth” actually is wide, wide open.

As we discussed, I’ve become a great believer in the truth as the bedrock of your storytelling, (and I always love to hear what pieces of your monologues people feel you just HAVE to have made up!) and it’s been really interesting, as your friend, to watch your personal journey into your Jewishness that was sparked by the Museum’s invitation to respond to Warhol’s paintings. I hope we wind up reflecting the full richness of that in the progress of the piece.

Let the wild rumpus begin. Or resume, I guess, is more better.