Yesterday I took my first shift at the Zen Hospice Project (ZHP) in San Francisco, where I am the newly appointed artist-in-residence. Since the kind of “artist” I am mostly involves talking about myself, people there (e.g., staff, along with relatives of the “residents” — the term used at ZHP instead of “patients”) understandably had (friendly) questions about what I might be up to: after all, a visual artist (say) might be expected to sit in a corner and do some sketching. What would a monologuist do?

Yesterday I took my first shift at the Zen Hospice Project (ZHP) in San Francisco, where I am the newly appointed artist-in-residence. Since the kind of “artist” I am mostly involves talking about myself, people there (e.g., staff, along with relatives of the “residents” — the term used at ZHP instead of “patients”) understandably had (friendly) questions about what I might be up to: after all, a visual artist (say) might be expected to sit in a corner and do some sketching. What would a monologuist do?

Well, it turns out, based on my first day, that what I do is be there. Which was, for me, an incredibly profound experience. Every moment I felt privileged — blessed — to be included in this remarkable community.

When I arrived for my shift (the volunteers work in three-hour shifts, preceded and followed by hour-long shift-change meetings), I learned that there were, at the moment, no residents! Which is apparently a very unusual occurrence. Was it something I’d said? This sounds incredibly weird even as I type it, but there’s an eeriness to a hospice that has no patients in it. (I think I’m going to use the “p” word from time to time.) Kind of an almost unbearable lightness. For the moment, this lovely house was … just a lovely house!

Except, of course, nurses and other staff members were still there. And also — incredibly, to me, though this obviously happens regularly at the hospice — there was a person who was already dead. She was a tiny, elderly woman, who had died only a few days after arriving there. I first observed the bathing ceremony: Still lying in her bed in her pretty room at the hospice — clothed — with her hands crossed and her mouth (this was a powerful thing to see) agape, she was surrounded by her three grown children and what I took to be a son-in-law. An RN named Jeff, who with his shaved-bald head and liquidly soulful eyes is someone you’d pick out of a lineup as who you’d want to run your death ceremony, made a gong-like sound by hitting a bowl three times with a kind of mallet. Explaining everything as he was doing it, he simultaneously emptied two carafes — one containing water, the other a kind of tea made from a spice that, he said, had long been used at death ceremonies by Native Americans from the area — into a bowl. He explained to the family members that anyone was free to do what he was about to do: dip a washcloth in the bowl and ceremonially wash the dead woman’s feet, hands, and face (he explained that her body had already been bathed completely by staff).

The family members seemed reluctant to participate in this way — which was fine. That’s one thing that I really appreciated about the ceremony: the non-pushiness of it. A lot of this non-pushiness came from Jeff: he made everyone feel okay just to be, and do, whatever was natural.

Everybody, I’m learning, responds differently to the death of a loved one. This is, to me, something that is both remarkable and — when I think about it — also unremarkable, in the sense that we are all different individuals, with our own quirks. It is, perhaps, the suppression of those quirks — the denial of our unique individuality — that makes so many ceremonies seem so false, so stuffy. Years ago, when my father died, I felt, at the funeral, as if we family members were almost like extras — and, for that matter, that Dad himself was kind of a prop: Paul Kornbluth, in the role of the dead person. In a way, I’ve spent much of my life since then trying, through storytelling, to restore his astonishing individuality. Yesterday, as this tiny, old — now dead — woman lay there, no platitudes were said about her. She was being celebrated, and her passing was being noted, and everyone could feel it in their own way — while at the same time being in the presence of others who were doing their own feeling.

A body that is no longer animated by breath, by hope, by love, is no longer a person: that was my experience yesterday. I realize that this probably should seem obvious — but I guess it wasn’t obvious to me, until I experienced it.

Another thing that struck me profoundly, but is also (I guess) obvious: death is a totally natural part of life. Death has always felt, to me, kind of like the sun: something that’s there, but you don’t (can’t?) look at. Well, you can look at it. You can look at it with the same eyes, and mind and heart, that take in the infinitely astonishing joyful miracle of a child’s birth. And you can feel what you feel, and that’s you, and no one else should be able to tell you how or what to feel. How we experience death — others’, and our own — is (I think) an important part of our personal autonomy. Also: When we make death a separate category from life, we tear a deep gash into the fabric of our existence, and bear the pain — and the sense of incompleteness — from that fissure through all our days.

To put it in wonkish terms: In the program of life, death is not a bug — it’s a feature.

A short time later, downstairs — as the imposingly enormous and courteous guy from the mortuary went about moving the body from the room upstairs — one of the woman’s sons approached me. “Excuse me,” he said, “but I wonder if you could tell me the significance of ringing the bell three times?”

I confessed to him, somewhat sheepishly, that this was my first day, and I didn’t know — but told him that every meeting I’d attended at the hospice began with three dings and then 10 minutes of “sitting” (meditating), which itself was followed by three dings. The guy nodded. Then he smiled a little smile: “I think I’ve seen them do it on Star Trek.”

I smiled back: “Well, then we know it’s got gravitas.”

I went off to try to find someone who could tell me why the bell-bowl had been rung three times. The hospice was less populated than usual, due to the paucity of residents to be cared for, and I couldn’t find anyone who knew. Everyone — including the family members — assumed that Jeff would know: I mean, he’s bald, and he’s spiritual! Finally, I saw Jeff descending the stairs, carrying the bowl and other objects from the ceremony.

“Jeff,” I said, “can I just ask you a quick question?”

With a touch of weariness, he said, “No, Josh, I do not know why we ring it three times!”

So clearly the word had gotten around that I was investigating the issue. And I thought: Okay, it’s time to stop asking about this.

Everyone next gathered outside, in a kind of garden area, for the second part of the death ceremony, in which people lay rose petals on the body before it (she) is taken away by the gi-normous mortuarian and his regular-sized pal. I told the family members that, based on my researches, the Star Trek theory was clearly in the lead. One of the daughters said, “We should Google it!”

Well, anyone who has been around me recently knows that I’m fairly obsessed with asking questions aloud to my new Android phone. So excitedly, I pulled out my phone and said, “Okay, Google now!” (which makes it blurble to life). I didn’t know how to word the question, so I looked desperately over to the family members, one of whom whispered, “Why three gongs at a Zen ceremony?”

So I said that into my phone, and after some more glurgling, it typed out: “Why three dongs at a Zen ceremony?”

I looked up from my phone apologetically. I told the family members that, while Google was taking our question in a fascinating and unexpected direction, it seemed perhaps best to leave the matter be for now. They readily agreed.

(For what it’s worth, this is my current theory of why three: Why not three?)

Later, after the body had been taken away and the family members had quietly and politely said their good-byes to us, I found out that this tiny old woman had, in life, been quite the spitfire. In fact, not long before her final bout with cancer, she had loved going to the gym to Zumba! And suddenly, in my mind, that dead body was animated into the living person she had been: I pictured her in tights — in the front row, dammit! — Zumba-ing like all get-out!

She’s dead now — but my God, she lived! She lived on this Earth! And she rhythmically swung her hips, and she smiled and sweated, and I bet everyone loved being in class with her.

About an hour later a new resident arrived. After spending a couple of hours in his vicinity, I can already tell you that he is a remarkable person, with a deeply loving son and beautiful grandchildren. I can report that I saw his young granddaughter tenderly stroke the hair of her even-younger brother. I hope and pray that this man will still be there on Friday, when I return to the hospice for my next shift.

In the meantime, may we who are currently living take every opportunity to Zumba like crazy! Turn the dial up to 12! Bust a move!

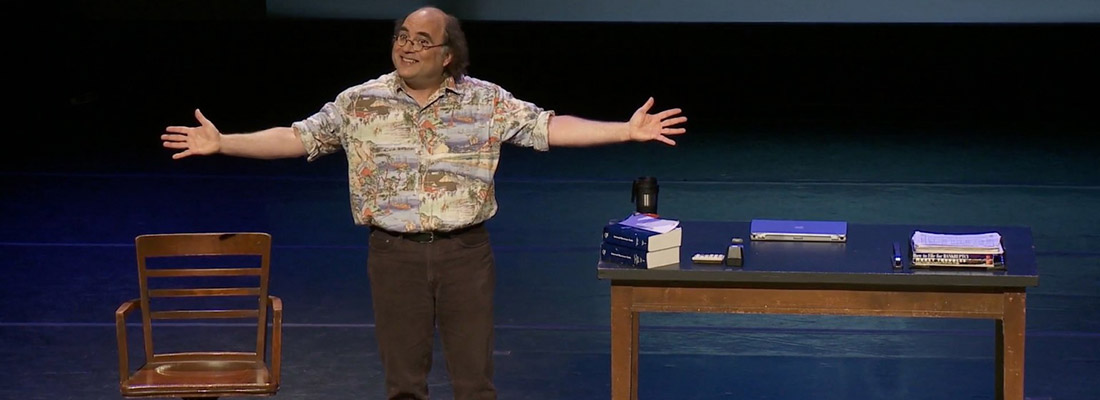

[I will be doing a solo performance on Oct. 1 as a benefit for the Zen Hospice Project. In the meantime, I plan to continue blogging here, as well as improvising about my experiences at some lovely Bay Area theater, and even — tech gods permitting — recording a regular podcast. Details to come, in this space.]

Josh

OMG, I cannot believe you’re blogging and possibly gigging about my dream job. Really?!? 😉 (I currently work as an RN but am interested in working in hospice care but thought I should do some volunteer work in the field) I’ve applied 2x to the volunteer Zen Hospice Program and for different reasons and mix ups and whatnot, it hasn’t happened yet. After reading your blog, I am inspired to keep knocking on the Zen Hospice door, not death’s door, hospice door.

Hey, Jacqueline:

Thanks so much for your wonderful comment!! I really hope you get to volunteer at ZHP — it’s an amazing place.

By the way, I’ll be starting with my hospice-related improvs next week: http://themarsh.org/berkeley/zen-hospice/.