Monologues

I do a few things, but when you come right down to it, ich bin ein monologuist. I started performing my autobiographical stage pieces in 1989, when I was 30 and feeling pretty desperate to start a career in something. Fortunately, monologuing took, and it remains a joy for me to do it for a living. I start with a simple idea — math, say, or democracy — and begin improvising in front of small audiences. My first audience was the friends and family of my friend Charlie Varon; he’d invited me to join him in an afternoon of trying out new material at Modern Times bookstore, in San Francisco’s Mission District. They liked my stories of growing up Communist in New York, and I was on my way.

I was working as a secretary at the time, for two lawyer brothers named Erlach. A friend told me that there was a little theater in North Beach run by the legendary Enrico Banducci, who had run the hungry i club back in the ’50s and ’60s, and had helped discover and nurture great comic talents like Richard Pryor and Mort Sahl. Later, after he lost that club, he opened Enrico’s, down the block; eventually, he lost Enrico’s as well. Now he was at a club across the street, called Banducci’s — though as it turned out, he didn’t own the place: they were just using his name, while he worked as the cook. Though they did let him run the tiny theater in the basement, which he called Enrico Banducci’s hungry id. It was a tiny, narrow, brick-lined space, with the owner’s white Camaro improbably bolted upside-down to the ceiling. Through a little door in the back was a “wine cellar,” with plastic vines clipped to the walls, which they rented out for stag parties. I went to audition for Enrico, telling him stories about my parents and their friends while he smoked a cigar and laughed. The next day I returned to negotiate my deal, accompanied by Ray Erlach. We sat down at the bar with Enrico, who offered me the free use of the theater; I could take any money from ticket-buyers, and he would keep all the money from serving food and drinks. Thrilled, I immediately said yes. As we walked back down to the Erlachs’ offices, Ray made me promise him that I would never again do my own negotiating — delicately, he suggested that this was not among my strengths.

Josh Kornbluth’s Daily World

… was the title I ended up choosing for my first piece, which opened at Enrico Banducci’s hungry id to an enthusiastic audience of a few friends. (Among the rejected titles: Leaves of Korn, which was summarily thumbs-downed by my movie-critic pal Mike Sragow and his wife, Glenda Hobbs.) As the opening night approached, I had little notion what the show would be about. Oh, I had plenty of ideas! But I didn’t know how to choose from among all the stories I wanted to tell.

At some point I decided that instead of writing a script for the show — which I was clearly unable to do — I would improvise. I didn’t know how long I could improvise, though, so I asked a jazz-musician friend, Bob Brumbeloe, to put together a little combo that could open and close for me (no matter how long, or short, my set turned out to be). Good call on my part: My early sets, as I recall, lasted 15 minutes or so. I’d taped a big piece of butcher paper on the side of the stage, on which I’d scrawled my many possible story ideas — each in a little bubble, with bubbles connected to other bubbles by scraggly lines to indicate possible links between stories. The paper could only be deciphered from up close, and in my nervousness I was planted in the center of the stage, so I never actually referred to it. Still, over the weeks, a throughline emerged: about what my parents told me about Communism, and about my childhood efforts to lead a Communist revolution.

Audiences were small, sometimes nonexistent. Once, as the Brumbeloe Trio played their opening set to an entirely empty house, I headed down Broadway to the famed City Lights bookshop (I have a thing for great independent bookstores), went downstairs to their basement section and persuaded half a dozen browsers to return with me to the hungry id. Turned out two of them were German tourists who spoke no English, but still, at least I had bodies out there. Occasionally I would benefit from the fact that Enrico’s original hungry i club, down the block, was still in business, albeit as a strip joint; every once in a while, a couple of inebriated fellows would stumble into the hungry id — eventually, after hearing me talk about my Marxist family for a while, they’d realize that I wasn’t a female stripper and stumble out. I’d realize their mistake, but still some part of me would be disappointed that I hadn’t won them over anyway.

Evy Warshawsky, who was booking the New Performance Gallery in the Mission, came to one of my performances with her husband, Morrie, and afterwards she invited me to take my show to the NPG (which was dark at that point in the summer). At the NPG, my improvs became longer and longer — to the point that the trio’s drummer sometimes had too much to drink during their long break and simply didn’t return. I started to see a modest increase in the size of my audiences — up to, say, 20 or 30 a night. Then I got a few nice reviews, and one day the crowd was suddenly over 120; the theater staff had to scramble for extra chairs.

A key moment: One evening, I was about to launch into the show ending I’d worked out with Bob and his colleagues: kind of a lounge-lizardy medley of the leftie songs of my childhood, with an intentionally cheesy “The Internationale” as the finale. It tended to be well-received, and ended the show on an upbeat note. But on this particular night I felt particularly close to the audience — comfortable, intimate — and so, on an impulse, I told them that instead of doing my usual ending, I wanted to tell the real story of my father’s funeral. The weird thing is, I’d never told the story to anyone — not even my closest friends. The crowd nodded encouragingly (at least, that’s how I remember it!), and I told the funeral story. That night I learned — or began to learn (I’m still learning this) — that there’s no limit to how deep an audience will go, if you have the courage to go there yourself. My own courage is occasional and fleeting, but I try to summon it periodically as I develop each of my pieces.

Daily World ended up running over six months. I had found a career — though not yet one that would allow me to quit my day job.

Haiku Tunnel

… came out of that day job. At this point, in 1990, I was still working as a secretary — now at a large firm called Pillsbury Madison & Sutro (or PMS). At The Marsh — then, as now, a wonderful resource for aspiring monologuists — I began doing improvs about a slightly fictionalized version of the firm, which I called Schuyler & Mitchell (S&M). For the first time I started working with a director — in this case, David Ford, whom I’d met backstage at a Shakespeare play. At David’s lovely apartment, which he shared with his talented actress wife, Anne Darragh, and their two hyperactive cats, he helped me edit the storyline I was developing in the improvs: A great temp (me) goes “perm” for a scary tax lawyer at S&M. When his boss gives him 85 very important letters to mail out, he neglects to do so — and spends most of the rest of the story trying to cover up his crime.

The title, Haiku Tunnel, came from an earlier temp job I’d had. An engineering firm had hired me to type up all the specs for a tunnel that was to go through a mountain in Hawaii. In the course of typing these specs, I’d gone into a deep depression. And in fact, depression is, in a way, the real subject of this piece: it’s about going from stuckness to taking a first, tentative step towards action — in this case, mailing some letters. At least, that’s what I think it’s about. Sometimes.

Haiku Tunnel opened at the Solo Mio Festival that fall, then — following warm reviews — ran for a long time at the Climate Theatre. Later it became the first completed show (as opposed to a work-in-progress) to run at The Marsh. And, to my relief, it showed me that I could hold an audience’s attention with a story that had nothing to do with my fascinating parents or their colorful friends.

Still, I wasn’t ready to give up my day job. Not till my brother Jake persuaded me to do so the following summer, as I was developing my third show, The Moisture Seekers.

The Moisture Seekers

This piece, which debuted at the 1991 Solo Mio Festival and later ran at the Climate and elsewhere, took its strange title from a condition I’d thought I had, but which turned out to be psychosomatic. Back when I’d been typing up the specs for the Haiku Tunnel, I’d suddenly felt as though my mouth had gone dry and numb. I did some research on these symptoms at a medical library, and discovered that there was something called Sjögren’s Syndrome; and in this file I found a newsletter for Sjögren’s sufferers, called “The Moisture Seekers.” It was a Eureka! moment: I instantly decided my next piece would be called The Moisture Seekers. But when I told people this title, they assumed that it was going to be about sex. I’d explain to them that no, the piece was actually going to be about a chronic disease in which white blood cells attacked one’s moisture-producing glands. Invariably, they would look disappointed. So finally I gave in and made it a monologue about sex.

My collaborators on this piece were my brother Jake and my friend John Bellucci (not the late comedian John Belushi — nor, for that matter, the ravishing Italian actress Monica Bellucci). They did a beautiful job. The Moisture Seekers opened in the fall of 1991 at Solo Mio, and later ran at the Climate and elsewhere.

I had three pieces! And at last I was a full-time performer.

Red Diaper Baby

A call came from the Second Stage in New York, a fine Off-Broadway theater. They’d been hearing about me from people who’d seen me in the Bay Area, and they’d had a production fall through when the star got a role on a TV show. Would I be interested in filling that slot?

Yes, I would. Holy shit! The big time!

They wanted me to combine Daily World and The Moisture Seekers into a new piece, which we ended up calling Red Diaper Baby. They hired Josh Mostel, the talented actor son of the late, great, crazy Zero Mostel, to direct. To alleviate any confusion, Josh announced at the outset of rehearsals that I would be known as “Josh” and he as “-ua.” My memories of our rehearsals are dominated by the image of “-ua” telling riotous tales about his dad, along with numerous war stories from his life in theater and film.

The run at Second Stage went very well, and afterwards an acquaintance of mine — the genius juggler-comic Michael Davis, to whom I’d been introduced after a performance — kindly agreed to produce an extended New York run, at the Actors’ Playhouse in Greenwich Village. My girlfriend, Sara, surprised me by flying across the country during a break in her school-teaching duties. We went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and played numerous games of mini-basketball at a neighborhood bar; it was a pretty blissful time.

Somewhere in there, Hollywood producers got interested in turning Red Diaper Baby and Haiku Tunnel into feature films — but that’s another story.

The Mathematics of Change

Butcher paper was finally put to proper use in the development of this show — a collaboration with John Bellucci. John and I shuttled between his town, L.A., and mine, S.F., as we approached the always dreaded (and necessary) opening night (this time, as part of the 1994 Solo Mio fest). There were lots of ideas floating around, and lots of mathematical tricks and squiggles, and John took to scrawling them on big pieces of paper and taping them up everywhere. John is one of the best actors I have ever seen, and even in his role as director-collaborator his actorly athletic and intellectual agility inspired me to push through countless creative blocks.

The story was ostensibly about my failure to grasp calculus during my freshman year at Princeton — but for John and me, both survivors of chubby New York Jewish childhoods, it was also very much about loneliness and failure. I still love to perform The Mathematics of Change, and these days I tend to notice how isolated my character is — even for a monologue! — and shiver at my recollections of how desperately I had wanted to be great at something. At college I was just beginning to learn how much better everyone else was at everything than I was — with the possible exception of one dubious skill: being myself.

Pumping Copy

I worked on this piece — about my years as a copy editor in my early 20s — for a few difficult months, in the mid-’90s. And even though it ran at The Marsh for a while, I never really figured it out.

I probably should have paid better heed to the dictum of my first editor-in-chief, Jimmy Weinstein of In These Times: “When in doubt, take it out.” Or even to my own instant corollary: “It’s a sin to leave it in.”

One day I want to come back to Pumping Copy and figure it out — perhaps renaming it The Rules of Editing.

Ben Franklin: Unplugged

With a phone call, my life changed. It must have been sometime in ‘97, when my son was in utero (not my utero, of course!). After the disappointment of the abbreviated Pumping Copy run, I was grasping for ideas. Maybe, I thought, my autobiography had run its course. And I was shaving one day when — almost mystically — the steam parted and I saw myself in the mirror and had a realization: I look like Ben Franklin! Might it be possible for me, I wondered, to put together one of those one-man shows, like Hal Holbrook’s perpetually running Mark Twain Tonight!, in which a famous dead person appears onstage and charms and beguiles audiences with his wit?

There were a couple of impediments that came immediately to mind: 1) I knew practically nothing about Franklin, except that he had (perhaps) once flown a kite; and 2) I’d never really played anyone besides myself. I asked Tony Taccone, artistic director of the Berkeley Rep, for any suggestions about someone I could work with to explore this new idea, and he instantly recommended David Dower. I had met David very briefly several years earlier, when my great friend Scott Rosenberg — then the theater critic of the San Francisco Examiner — brought me to see a performance by The Z Collective, of which Dower was a presiding collectivizer and director. Now, years later, David had transformed the collective into The Z Space, an extraordinary resource center that supported theater artists, in myriad ways, through the completion of their projects.

Brazenly, I called David’s home phone. His brilliant wife, Denice Stephenson (now a great friend as well), picked up, and I tremulously asked whether David was home. She passed the phone to him, and I launched right into my pitch: I wanted to try making a monologue in which I portrayed Ben Franklin, even though I’d never done this sort of thing before. Would he be my director and collaborator? For reasons I’ll never quite understand — perhaps through some sort of semi-secular, semi-divine intervention — he instantly said yes.

Thus began a friendship that continues strong through the present day. Without realizing it at the time, I had moved into a new phase of my work — one in which I wouldn’t always have to tell audiences about every aspect of my personal life. Among other things, this allowed me to funnel my passions into my work without (I hope) intruding too much into the privacy of my dear, beautiful son, whom I wished to move through the world unshadowed by a fictional version of himself propagated by his performer dad.

Franklin had a son, too — though their relationship, which began as a close one, tragically deteriorated. William Franklin, Royal Governor of New Jersey, chose to remain an ardent Loyalist throughout the American Revolution — causing an irreparable split from his famous father. After I’d been working with David for a little while, I was drawn to this father-son relationship between Ben and William: at the time, I was a father-to-be myself, and my relationship with my own late father had been an overwhelming aspect of my life and work. David gently and skillfully “allowed” me to discover that I need not — and probably should not — do Hal Holbrook-type shows, but instead could expand my own autobiographical accounts to include political, social, and historical issues of enormous interest to me (and, we hoped, to audiences as well).

Ben Franklin: Unplugged — which eventually opened in ’98 — had a long, bumpy development as David worked with me to develop this new type of piece. Ultimately, we were both thrilled at how it turned out: a story that was, yes, partly about me and my sometimes neurotic concerns, but also about that fascinating, tortured relationship between Ben and William — and, ultimately, about how I, a third-generation American Jew, could feel so intensely connected to the celebrated seventh son of soap-making Puritans.

There was a first-generation American Jew who figures strongly in the story as well: Claude-Anne Lopez, a brilliant Franklinista. After being dazzled by her masterpiece, the book Mon Cher Papa: Franklin and the Ladies of Paris, I sought out this charming Belgian émigré (she barely escaped the Nazis) when passing through New Haven on tour. (She lived near Yale, where she had worked for many years at the Benjamin Franklin Papers.) Little did either of us know at the time that she would become a key figure in my new show — my charming (and much prettier) Yoda-type guide to the wonders of the Franklin archives. (Sadly, Claude died in 2012 — so now no one calls me “Joshua the Bear,” the nickname she gave me when I allowed that I enjoyed giving bear hugs.)

Love & Taxes

My second collaboration with David Dower — in what, at some point, he revealed to me he’d always thought of as a “Citizen Josh” Trilogy — was a piece that took as its launching point a horrible, awful, terrible tax problem I’d had a few years back. What especially interested us about this narrative was its potential for drawing audiences into a tax horror story while subtly (we hoped!) setting them up for what was a rabidly pro-tax message.

Love & Taxes — which was initially developed at the magical Sundance Theatre Lab, then later at The Z Space — begins as the sad tale of a tax delinquent who tries his best to get out of his obligations (both financial and romantic). But by the end of the story, his attitudes have changed considerably. Starting in the summer of ’02 at Sundance, David and I followed our usual, torturous process of endless discussions (between him and me, and between me and a host of incredible tax people) and endless improvs (performed by me for gracious audiences in many locations). I now think that taxation is the coolest topic on the planet — with the possible exception of love (”lovation”?).

After some initial bumpiness, a run of Love & Taxes in 2004 (I think) at the Magic Theater in San Francisco (I’m sure) received a gratifyingly positive response. It was also notable, for me, as the time I first met Jonny and Hillary Reinis. I had known of Jonny (and his wife Hillary, also his business partner) for years, as a legendary Bay Area producer with multiple Tony Awards and much else to his credit. When they introduced themselves to me after a performance at the Magic, and Jonny asked whether he might produce my next run of the show (at the Berkeley Rep), it was all I could do to squeak out a stunned “Yes!!!” Jonny continued as my theatrical producer for many years, and though we’re not currently connected professionally, he and Hillary — whether they realize it or not — are stuck with me for life. Which would make me as inevitable as … well, you know.

Citizen Josh

My third collaboration with director David Dower was, like Love & Taxes, developed first at the Sundance Theatre Lab and then at The Z Space. Citizen Josh opened at the Magic Theatre in San Francisco (around 2006 or ’07, maybe?), followed by a lovely run at the Berkeley Rep. The new show grew out of my distress at the anemic condition of American democracy — and my nagging suspicion that our society’s political health depended on the active participation of all its citizens, even ones as habitually passive as myself. The show incorporated enormous contributions from producer Jonny Reinis, designer Alex Nichols, and composer Marco d’Ambrosio, as well as stage manager (and all-around fixer) Andrew Packard.

One of the quirks of that show is that it also served as my long-overdue senior thesis for Princeton. (Well, that was the goal — actually, Princeton’s Politics department is making me add a more thesis-y addendum.) You can read an article I wrote about the experience — as well as catch both a video and audio excerpt from Citizen Josh — by clicking here.

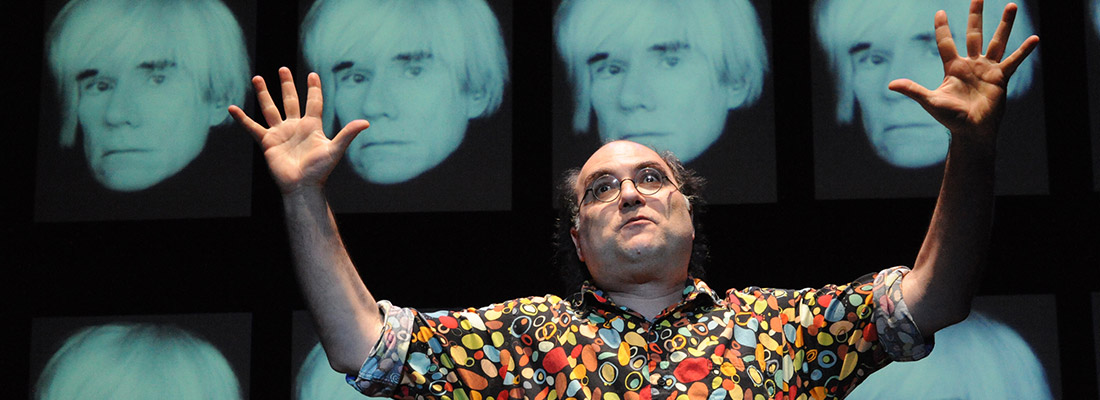

Andy Warhol: Good for the Jews?

My first commission!

Dan Schifrin of the Contemporary Jewish Museum asked me to create a short piece responding to one of their exhibits, “Warhol’s Jews: Ten Portraits Reconsidered.” The result, a presentation titled Andy Warhol: Good for the Jews (the title was Dan’s brainstorm as well), had a lovely little run at the CJM.

After that, David Dower and I worked to expand Warhol into a full-length monologue, which opened at Theater J in Washington, D.C., after an intense, brief rehearsal period. The brevity was the result of a continuing geographic fact: David was now working on the East Coast (at the time, at the Arena Stage in D.C.) while I remained in the Bay Area— and it had become more and more difficult for us to schedule times (and places) to work together. So all the collaborators — David and me, along with lighting and projections designer Alex Nichols and composer Marco d’Ambrosio — essentially crammed: all of us feverishly improvising, bouncing off of one another, revising, repeating. I think there was a point at which Marco hadn’t slept in a couple of days, yet was still going strong, writing and rewriting musical cues and dealing with various technical issues.

Warhol later moved back to the Bay Area, where it played at the Jewish Theater San Francisco — which had grown out of A Traveling Jewish Theater. (This theater is one of several I have performed at that shut their doors for good soon after; I’ve tried not to think too deeply about how responsible I might have been for these closures!) It has gone on to tour a bit around the country — but I’m very hopeful of a long touring life to come for this piece, which is very close to my heart (and soul).

The subject matter of Warhol is … well, on the one hand, the life and work of Andy Warhol, but on the other, my midlife discovery of Judaism. Which is to say, a rediscovery of an aspect of myself that I hadn’t previously examined with any intensity. I’ve always been proud to be a Jew — it’s a huge cultural part of who I am (and who my parents were). But since I don’t believe in God, the religious and mystical dimensions of Judaism have felt almost verboten to me.

Then Dan Schifrin at the CJM suggested that — as part of my researches toward the Warhol piece (specifically, the subject of one of Warhol’s portraits, theologian and philosopher Martin Buber) — I chat with his friend Menachem Creditor, the rabbi of a nearby Berkeley shul, Congregation Netivot Shalom. Thus began a friendship that has affected my life in the deepest ways. Not only did Menachem become a valuable resource to me, as someone who really knows the Jewish stuff, but he also inspired me to continue exploring Judaism, even after the Warhol show was completed.

What made all this possible for me was Menachem’s definition of God, as he described it to me one day: The collective potential of the human imagination. Thinking of God in this way (or in similar ways) — rather than as, say, a bearded old man in the sky — collapsed the distance between my atheist self and the Biblical writings (as well as the fascinating tales of Jewish mysticism). I didn’t feel the need to continue separating the secular and spiritual sides of myself — or to see religious people as The Other. (It’s a subject that I’m still very much in the process of working out, and may well be doing so for the rest of my life.)

One day, on an impulse, I asked Menachem if he would bar mitzvah me. (I hadn’t had a bar mitzvah at the traditional age of 13.) Not only did he agree to instruct me toward my bar mitzvah, but (in typical fashion) he made the whole thing into a series of public events. First we opened up our learning together to our respective e-lists — offering a class at shul that we called My Big Fat Jewish Learning. Amazingly, 60 people or so ended up signing up for the course. Then Menachem arranged for my wife and son and me to join him and his family, along with 18 or so other folks, on a summer trip to Israel — in the middle of which, on a water tower in the Negev Desert, he led my bar mitzvah ceremony. (I was 52 at the time.) The Torah we used, one that he had borrowed from a synagogue in Jerusalem, had been rescued by Jewish partisans in Lithuania during the Holocaust. It was a deeply moving ceremony — and paradoxically, it made me feel a special closeness with my completely secular Jewish parents, as well as with my dear (not Jewish) wife and our beautiful son.

I described my middle-aged bar mitzvah in my next piece — my second commission:

Sea of Reeds

This commission came from producer Jonny Reinis and the Shotgun Players — a wildly wonderful theater company in Berkeley, now housed at the Ashby Stage. Shotgun artistic director Patrick Dooley — kind of a human vector of energy, creativity, and collaboration — sparked to an idea I had: of combining my continuing explorations of Judaism with my longtime struggles to play the oboe (which involve the Sisyphean task of continually trying to make oboe reeds). But Patrick — who likes to really populate his relatively small stage — said he wanted this piece to be the first in which I wasn’t the only performer.

Eventually, we put together a cast with me and one other actor — the amazing Amy Resnick, who had earlier appeared in my Haiku Tunnel movie — along with four talented young musician-actors: El Beh (cello and vocals), Jonathan Kepke (piano), Olive Mitra (bass and percussion — also our bandleader), and Eli Wirtschafter (fiddle). We played music composed by Marco d’Ambrosio that — incredibly — combined elements of Bach, klezmer, and ancient Jewish tunes. Nina Ball designed a lovely, deceptively simple set (inspired, in part, by her joining me at shul one Saturday morning). We told stories from the Torah, and from my Jewish journey. And I made oboe reeds! Onstage!

It was tons of fun! But one thing I think I learned from the experience was that I’m best as a monologuist: even though Amy and the rest taught me a lot about acting with others onstage, it still doesn’t feel totally natural to me. Also, the prospect of touring with more people than just me seemed (and seems) daunting, financially and logistically. So my plan is to continue working on Sea of Reeds, reducing it to a monologue (with either live or recorded musical accompaniment) and continuing to work out my complex attitudes toward Judaism, Israel, and oboe-playing.

During the rehearsal process for Sea of Reeds, David Dower told me that this would have to be our last collaboration for a while. He had just gotten too busy, and we were across a continent from each other. By this point David had moved on to Boston, where he is now artistic director at ArtsEmerson. So after nearly 20 years of a glorious collaboration with Mr. Dower, I am now working with a fantastic new director, Casey Stangl, and an amazing dramaturg, Aaron Loeb, on …

The Bottomless Bowl

In 2014 — around the time I was turning 55, the age my father had been when he had the devastating stroke that eventually killed him — I was invited to be the very first artist-in-residence at the Zen Hospice Project in San Francisco. Almost from the moment I set foot inside their lovely Guest House, I fell in love with the place, with its people and with its spirit. After my artist-in-residency was completed, I asked if I could continue as a volunteer — and they said yes!

I’m working on a monologue about this experience — and about what it opened up in me, emotionally — titled The Bottomless Bowl. Stay tuned!

Citizen Brain

In the fall of 2016 I dashed off an email to Dr. Bruce Miller, director of UCSF’s Memory and Aging Center (MAC), a world-class institution for the study and treatment of brain disease. Two of my pals, the poet Jane Hirshfield and the clown/monologuist Geoff Hoyle, had been Visiting Artists at the MAC — and, after I’d had such a life-changing experience as artist-in-residence at the Zen Hospice Project, I was wondering if I could put my hat in the ring for this position.

At our initial meeting in his office, Bruce told me about a brand-new thing that was just then springing to life: the Global Brain Health Institute (GBHI). Based in two places — the MAC in San Francisco and the Neurology Dept. at Trinity College Dublin — GBHI runs a fellowship program that trains people from diverse backgrounds and then sends them back out to promote equity in brain health. Bruce invited me to apply for a fellowship and, happily, I was accepted — leading to four of the most exciting and productive years of my life.

As I began my fellowship, two dire situations were dominating my thoughts: My beloved stepfather, Frank Rosen, had developed Alzheimer’s, and a fascist narcissist from Queens had become president of the United States. Immersed as I was in the subject of brain disease, it was perhaps inevitable that I came to a realization: both my stepdad and our nation’s politics were suffering from dementia.

Thus were the seeds sown for my latest monologue, Citizen Brain, which I wrote in collaboration with director Casey Stangl and dramaturg Aaron Loeb. Commissioned by the Shotgun Players, it was scheduled to premiere at the Ashby Stage in Berkeley in October 2020. And it did premiere then — though, because of the pandemic, that debut run happened over Zoom, as I performed from my living room. Recently, I finally got to do the show for live audiences, as I began performing it in friends’ backyards. I had a blast, and hope to do more of these backyard gigs once we get past the Bay Area’s rainy winter season. And who knows? Maybe one day I’ll be able to tour indoor theaters again!

Film

In 1992 I was performing my show Red Diaper Baby in New York, and my then-agent told me that someone at Universal Pictures was interested in optioning it. This news mostly thrilled me, but also terrified me: I had premonitions of Hollywood turning the story of my Communist parents into something sanitized, popularized. (God forbid I should make something that became popular!)

Indeed, Red Diaper Baby was optioned (that is, a company paid me for the exclusive rights, over a period of two years, to try turning it into a feature film) and, in an especially cool development, I was hired to write the screenplay. Thus began a period in which I tried to do the one thing that has most defeated me: Write Something Down.

The movie people were very nice to me, though it did sometimes feel that what they were aiming for — something intended for the mass market — was not, perhaps, what I was aiming for (something that would honor the complexity and beauty, along with the neuroses, of my upbringing). But again, I think the main problem was that I Had To Write Stuff Down.

When I’m trying to write, sitting at a computer (as I am now), my mind keeps trying to edit what’s coming out of it: there’s a weird kind of courtliness that I seem to try to go for — a filing down of the weird corners, crusts, and barnacles of my actual thinking. The way I’ve gotten around this self-censoring is to develop all my monologues in improvisations in front of audiences: in the presence of listening people, my filters mostly dissolve and words (too many) and stories spill out. Not so much when I’m by myself, typing.

So there I was, facing my laptop — in New York, in San Francisco, in L.A., in Berlin, even — and trying to create a screenplay. But really, trying to create a flow — just get the ideas out, the images out, which later I could edit (as with my monologues). And it was just so damned hard. …I mean, writing is hard — at least, based on all the Paris Review interviews I’ve read — but I had a flow in the monologuing process that I couldn’t seem to replicate with screenwriting.

And the option ran out, and no Red Diaper Baby narrative film has been made (yet!).

Similarly, during this period my other then-agent (yes, I had two — both at William Morris) brought me to the attention of a Hollywood producer, Michael Peyser, who came to see me perform a bunch of my shows in an L.A. storefront and got it into his head that another piece of mine, Haiku Tunnel, could be turned into a feature film. He was doing stuff with Miramax at the time, and suggested that they might want to make the movie a vehicle for some TV-show star. After agonizing over this for a night or so, I called Michael and said that, actually, I would like to star as me in the movie. A pause, and then he said: “Okay — that just makes it a different kind of movie.” Meaning: lower-budget, and perhaps with ancillary characters played by well-known actors.

But first Miramax had to see me perform. So Michael arranged for me to do the show, in its entirety, for Miramax staffers, including honcho/brothers Harvey and Bob Weinstein and (I was told) even the Weinsteins’ mom, Miriam. (My understanding is that Miramax was named after their parents, Miriam and Max.) I performed on the stage of the Miramax screening room in New York. At one point, during my performance, I (but not the audience) saw firefighters streaming into the restaurant next door — but my priorities were in order, so I kept performing without skipping a beat. … Afterward, Harvey, smoking a big cigar, told me he was going to make me a star. (I suspect that now, as he deservedly rots in jail for his numerous sex crimes, Harvey rarely reflects on my career trajectory.) Also, I heard that Miriam (whose birthday it was) thought I was a nice, funny Jewish boy.

Now I had two pieces optioned, and two screenplays I was working on. Alas, though I had tremendous writing help from my friend John (Not Belushi) Bellucci and lovely support from the Sundance Screenwriting Lab (for both screenplays), the Haiku Tunnel option (like the Red Diaper Baby one) passed without a film being made. Michael tried some other things, in the hopes of getting the movie done independently, but — despite a number of “pitches” that involved me performing the piece a few more times — nothing took.

And then my brother Jacob got involved. (This was several years later.) Jake had graduated from college and then, deciding he wanted to be a filmmaker, begun rapidly working his way up various film productions — first in the Bay Area, and then elsewhere as well. Jake got me thinking that maybe he and I could make the Haiku Tunnel movie ourselves, with film people he’d met on various jobs. It seemed impossible — we had no money, or filmmaking pedigree — but dang it if we didn’t do it. One huge part was that we were able to raise the money from local Bay Area investors — the most prominent one being David Fuchs, who became the executive producer. We also greatly benefitted from being able to do a several-week script-development workshop at the Z Space (founded by my then theatrical collaborator David Dower), in which we could try all kinds of stuff with actors, many of whom ended up in the actual movie.

Amazingly, we completed the film, and perhaps more amazingly, it got into Sundance; and, continuing with the amazingness theme, it was picked up by Sony Pictures Classics. Also amazing — though in a completely horrible way — the movie was released on Sept. 11, 2001 (forever putting to rest my habit of asking myself, “What could go wrong?”). Some critics loved it, some liked it, some absolutely hated it (and me) — and the whole release was basically a traumatic experience, against the infinitely traumatic backdrop of the awful tragedy of the Sept. 11 attacks.

And yet… Jake and I made our movie! With our friends! And it had beautiful work in it: the photography, the set design, the music, the acting by all the wonderful actors who joined me onscreen, the editing, the directing (Jake and I were listed as co-directors, but basically Jake directed it), the sound mixing by the sound-studs at Skywalker — and, to me, the spirit. Haiku Tunnel was a truly independent film, FUBU by Jew Bros. I’m really, really proud of it. And occasionally I run into someone who dug the movie, and that makes me feel really good.

And now, Jake and I have made a second movie (also based on a monologue of mine): Love & Taxes. It was released in 2017, and has a 100 percent “fresh” rating from Rotten Tomatoes! (Jake and I were quite relieved when there was no terrorist attack on opening night.) Like our first movie, Love & Taxes was completely homemade, funded by awesome local investors — a labor of love (and, yes, taxes).

“Love & Taxes” is now available on Video On Demand! Find it on Amazon, iTunes, VUDU and Google Play.

TV

About a decade ago, I got a call out of the blue inviting me to audition to host a new show that KQED, San Francisco’s public TV station, was planning. They’d already auditioned a bunch of people and were still casting about for possibilities — and someone thought of me, as a kind of what-the-hey wildcard to try out.

And then, amazingly (as I had no TV broadcasting experience), they chose me for the gig — and they named the program The Josh Kornbluth Show. (My suggestion had been Citizen Josh.)

The show ran for two years, and it was great fun. I got to interview a wide variety of authors, artists, sports figures, and politicians — along with one very passionate rescuer of bunny rabbits. Some of my favorites: the photographer Annie Leibowitz, actors Helen Mirren and Alan Alda, funny person Amy Sedaris, and conductor Michael Tilson Thomas (for whom I nervously played a passage from Stravinsky’s Firebird on my oboe — he was very gracious). California Senator Barbara Boxer showed up even though she had a really bad cold; she was plugging a romance novel (!) she’d written. I was very moved by my conversation with Chris Gardner, whose memoir The Pursuit of Happyness (which was adapted into a movie starring Will Smith) recounted his experiences raising a toddler while being homeless. Actor/director Delroy Lindo told me a really fun story about working with Gene Hackman on the David Mamet film Heist (which I love).

Everyone at KQED was incredibly cool and nice, and I was sad when the show got cancelled after its second season. I think if I’d gotten to keep going, I would have found a way to put more nuance into my appreciative-puppy-dog style of interviewing. But it was lovely while it lasted (plus I had an office — and health insurance!). For the first time, people on the street tended to recognize me (a lot more people watch public television than go to the little theaters I tend to perform in); truckers honked sometimes; and, touchingly, a woman from Latin America told me she’d learned to speak English from watching my show. (Did she end up talking like a scattered New York Jew? Our conversation wasn’t long enough for me to make that out.)

And a monologuist got a taste of being in dialogue! Maybe I’ll get to do it again someday: as far as I can tell, I’m as telegenic now as I was then.

Brain Stuff

I am currently a Senior Atlantic Fellow for Equity in Brain Health at the Global Brain Health Institute (GBHI). With producer Alex da Silva, I’ve been putting out a series of brain- and social-justice-related online videos, titled “Citizen Brain.” In addition, my fellowship has inspired a one-man show, also titled Citizen Brain (see above).

Community

Berkeley Energy Commission

A few years ago, Berkeley Mayor Tom Bates appointed me to the Berkeley Energy Commission. Contrary to rumors, no money changed hands at the time — though I might well have accepted some, had it been offered. In my (very educational) two years on the board, I learned that (a) energy policy is incredibly complicated and (b) government stuff moves slo-o-o-owly. It was a great privilege to be a part (albeit a minor one) of my local government for a while.

Benefits

If someone asks me to do a benefit, and I’m available that day and I can get there, I pretty much always say yes. Pete Seeger, one of my heroes, performed at every benefit he could (including one I attended, in my teens, when Pete was clearly very sick with the flu or something; he’d still taken the train down to New York City from upstate).

Here’s a partial list of some of the marvelous organizations I’ve done benefits for:

American Jewish World Service Benefit for Darfur Children

Berkeley Food & Housing Project

Berkeley Path Wanderers Association

Berkeley Sustainability Summit

California Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools

East Bay Jewish Community Center

Friends of the San Francisco Public Library

Measure A in Berkeley (for public school funding)

Measure FF in Berkeley (for branch libraries)

Barack Obama for President

Bernie Sanders for President

Opportunity for Independence (San Rafael, CA)