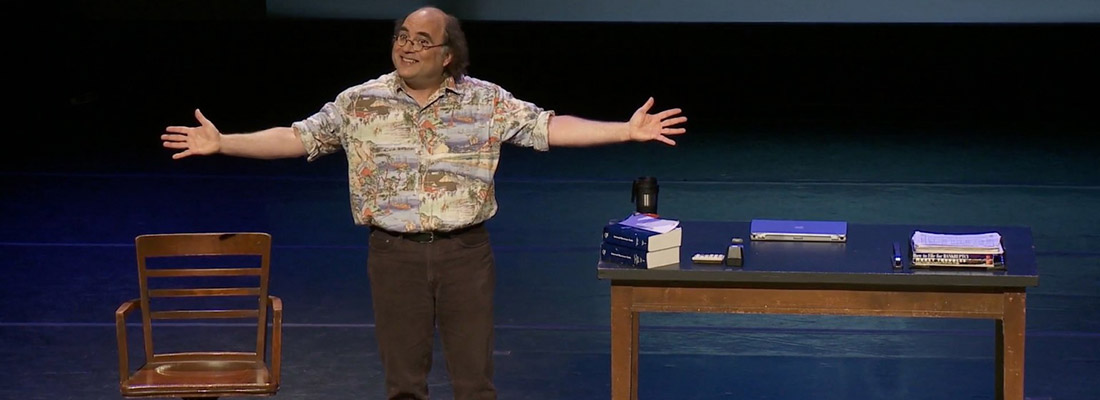

I have a mini-run coming up in January of my latest theater piece, Sea of Reeds, at the Jewish Community Center of San Francisco. (For tix & info, click here.) We had the initial run this past summer (at the Ashby Stage in Berkeley), and it was a blast — but I felt (I think everyone involved felt) the show could go deeper. I’m sure you could say that about all my shows … but there’s something in the subject matter of this particular show — growing older, coming to terms with my Jewishness, the complexities of the modern state of Israel — that seems to call especially loudly for more self-questioning.

I have a mini-run coming up in January of my latest theater piece, Sea of Reeds, at the Jewish Community Center of San Francisco. (For tix & info, click here.) We had the initial run this past summer (at the Ashby Stage in Berkeley), and it was a blast — but I felt (I think everyone involved felt) the show could go deeper. I’m sure you could say that about all my shows … but there’s something in the subject matter of this particular show — growing older, coming to terms with my Jewishness, the complexities of the modern state of Israel — that seems to call especially loudly for more self-questioning.

A challenge at this stage of the piece is that I actually have to write. In the past couple decades or so, I’ve developed all my shows through improvising — to audiences, and to my director-collaborators. This has turned out to be a cool way for me to generate material, as I never have to do it alone (like a real writer); also, this method has resulted in shows that sound like me: Since I develop them through talking, they tend to sound (and be) very natural — not too literary, or stilted (I hope!). But there’s another side to that coin: developing shows this way can also be limiting. For one thing, it’s hard to create non-monologue material in this manner. This was a big deal with Sea of Reeds, as Patrick Dooley — artistic director of the Shotgun Players of Berkeley, who commissioned the piece — specifically asked me to create a show that would have other performers on stage with me.

What ended up happening is this: For a year or so, I followed the usual process for developing a new monologue: improvising to small audiences, while doing research, taking notes, etc. But then, when it came time to “open up” the piece for the other performers (one actress-musician and four musician-actors), I didn’t know what to do! I’d never created a script before the run of a show — only transcripts that came after the run. But with multiple performers, you need to let them know, in advance, what you want them to do — so they can, you know, rehearse and memorize stuff. Fortunately, my director-collaborator, David Dower, saved the day — writing up material for the actress (the fabulous Amy Resnick) and the musicians to say (some of it adapted from videotapes my son did during our family trip to Israel). So I kind of developed my own lines in my usual, monologuing way, and the other material came from David (also, Amy improvised a bunch of great stuff).

Now, as we prepare to re-mount the show in January, David is far away, doing fantastic things that, alas, are not focused on me. And Patrick has made it clear to me that, especially given the restraints of time and money, I can’t indulge in my usual process (improvs, and more improvs). So I need to actually, you know, write stuff. … And, in truth, there’s another reason for me to try this (to me) novel approach: the subject matter is so difficult that it’s been really hard for me to try to work it out on my feet, in front of people. When I have an audience I feel protected — but also, I suppose, I feel a compulsion to try to entertain. Which, often, is a good thing — I want my shows (even the improvs) to be entertaining! But what if a subject raises strong mixed feelings in both me and my audience? Then what can happen is that my performer’s impulse to seek approval can get in the way of reaching a deeper truth.

I learned long ago that an audience in the theater is capable of holding much more complexity than I am capable of delivering. It has been my asymptotic goal to try to give them that deeper truth, as best I can. Now, with Sea of Reeds, I’m finally trying to get there the old-fashioned way — with written words. With Patrick’s and Amy’s help and encouragement, I’m generating an actual script, which we will then rehearse from. I cannot begin to tell you how terrifying this is to me! (Though I guess I’m trying to.) Words on a page (or screen) are, like Fredo to Michael Corleone, dead to me. But I am working on having the faith that they (or at least some of them) will come alive in performance. Or, to put it another way, I am trying not to visualize audiences rejecting this new stuff. Because now, for the first time (for me), the audience won’t be present at the creation of the lines — and thus won’t be able to validate any of the many choices that a writer has to make.

This feels appropriate for a show that (I think) is about the passionate need for dialogue. But try telling that to my frightened mind! Maybe when we say we want dialogue, sometimes what we really mean is that we want to feel evolved? Maybe real dialogue involves more discomfort than we’re willing to experience. I get older, and I see all the ways I have learned to make myself comfortable — this is who I am, these are the things I believe. Now I have a chance, a rare chance, to question those habits, maybe even change some of them. Will I be able to get myself to do so? I suppose writers — real writers — come up against this question all the time.

Yikes!