In the middle of my sophomore year at Princeton, in the late ’70s, I was at a loss for what major to declare. I’d flamed out in mathematics, followed by similar meltdowns in physics, biology, and chemistry. Now, it seemed, I had no other choice but to major in the humanities (something my father had always told me was unnecessary at college, since reading was something I could always do on my own). But which humanity? My friend David Remnick (now editor of the New Yorker, and still with amazingly good hair!) mentioned that he’d heard about a really cool political-theory professor named Sheldon Wolin. I looked the guy up in the course catalogue, and signed up for his class in Ancient Political Theory. It was thrilling — each lecture, seemingly improvised, made unexpected connections through time and geography. Prof. Wolin took us on a vital quest for real, participatory democracy; he made ancient political theory feel like the most contemporary subject imaginable.

In the middle of my sophomore year at Princeton, in the late ’70s, I was at a loss for what major to declare. I’d flamed out in mathematics, followed by similar meltdowns in physics, biology, and chemistry. Now, it seemed, I had no other choice but to major in the humanities (something my father had always told me was unnecessary at college, since reading was something I could always do on my own). But which humanity? My friend David Remnick (now editor of the New Yorker, and still with amazingly good hair!) mentioned that he’d heard about a really cool political-theory professor named Sheldon Wolin. I looked the guy up in the course catalogue, and signed up for his class in Ancient Political Theory. It was thrilling — each lecture, seemingly improvised, made unexpected connections through time and geography. Prof. Wolin took us on a vital quest for real, participatory democracy; he made ancient political theory feel like the most contemporary subject imaginable.

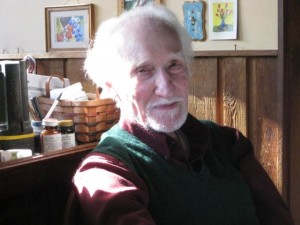

He had me at Plato! But I wanted more! I signed up as a Politics major — but really, I wanted to major in Wolin. As my advisor, he was gentle, Socratic, but always rigorous. He was a ubiquitous figure around campus, often walking his big shaggy white dog — the two of them moving, white-maned, serenely down a winding path. Wolin also was an activist — he believed that political theory had to include political action as well as thinking — and took great interest when a number of us became involved in the effort to get Princeton to divest its stocks in then-apartheid South Africa.

Here’s a perfect example of Wolin’s balance between scholarship and activism: We anti-apartheid students had taken over Nassau Hall, Princeton’s main administrative building. Wolin, one of the “faculty observers,” passed me as I leaned against a hallway wall. He complimented me on my participation in the protest, but then added, pointedly (though with a smile), “You are doing your reading as well, Josh, aren’t you?”

Well, no, I wasn’t. I was a terrible student. I’m a slow reader — that was one problem. Another was that I was still, at that age, determined to be a dutiful son to my Marxist parents and become a Marxist myself. Early on, I said to Wolin (quite innocently), “You are a Marxist, aren’t you?” He laughed, gently, and demurred. This perplexed me: why wouldn’t this brilliant radical theorist (his other great course that I took was Radical Political Theory) be the only kind of radical I considered to be legit? Now, decades later, I’m not sure what I am — a democratic-socialist-wannabe-capitalist? But at the time my political thinking was quite binary — either this or that — and I will always be grateful that Wolin never denigrated my beliefs, but rather kept asking me questions that made me ask my own questions.

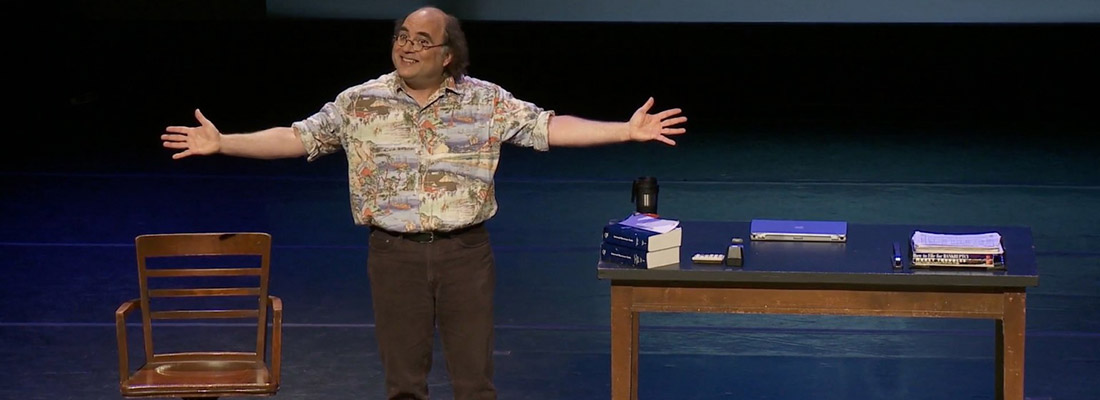

To my shame, in my senior year I froze and never got around to writing my senior thesis for Prof. Wolin. But decades later, on a whim, I reached Wolin where he was living at the time, in a forest in very northern California, and he agreed to continue advising me! (I describe the experience in my monologue Citizen Josh, which can be heard as part of my recent audiobook.) It was yet another act of kindness and generosity on his part.

My dear friend (and Berkeley neighbor) Brian Weiner is one of many, many students of Wolin’s who — unlike me — ended up becoming political theorists themselves. It’s a passionate, hyper-intellectual group, Wolin’s intellectual progeny. Another of the Wolinistas, Corey Robin, has written a wonderful appreciation of Wolin with an appropriate amount of erudition. Lacking that erudition myself, I can still try to carry on in the spirit that this great teacher tried imparting to me: engaging in politics with passion and as much intellectual honesty as I can summon. From Wolin I learned that democracy is precious and so very delicate — we all must try to nurture it, even when things seem hopeless. Like jazz musicians — like Prof. Wolin in the lecture hall — we have to keep improvising, doing our best, resisting marginalization, resisting intellectual (or actual) laziness.

I am so sad that he is gone, and I am so glad that I had him as a teacher. My heart goes out to his family and to his many, many friends, colleagues, and students.

Excellent remembrance, Josh. The best teachers expand and grow brighter in our memories.

Dear Josh,

My condolences to you for your grief in the passing of your beloved teacher/mentor. I love this, “I will always be grateful that Wolin never denigrated my beliefs, but rather kept asking me questions that made me ask my own questions.” Such a powerful, always renewing gift when we can receive it. As an artist and activist, you are a progenitor of this essential principal that the best of people evolve and live their character in the depth of the questions they ask themselves.

“From Wolin I learned that democracy is precious and so very delicate — we all must try to nurture it, even when things seem hopeless. Like jazz musicians — like Prof. Wolin in the lecture hall — we have to keep improvising, doing our best, resisting marginalization, resisting intellectual (or actual) laziness.”

Wow, such a beautifully turned expression of the working ideal that is democracy. Thank you for putting it so well that I know I will never forget it. What a legacy you have inherited — both from your parents, extraordinary people whose gifts you have shared so wonderfully — and from Prof. Wolin.

All good things and best wishes, may your heart be so full of the love that it will be a balm in your grief.