I briefly stick my nose above the surface of Buber-reading and script-doctoring to mention that I’ll be doing an improvisation this Thursday, March, 26, at 7 p.m. at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco. It’ll probably last one hour, and may or may not be in the gorgeous, asymmetrical “Yud” room. Click here for details.

This event is at the invitation of the CJM’s Writer In Residence & Director of Public Programs, Dan Schifrin, who both commissioned the Warhol show I did there recently and also came up with the title (Andy Warhol: Good for the Jews?). So at this point, when Dan comes up with wordings for things for me I just try to run with them. His suggested title for this improv: “I Brake for Buber.” And his event description runs as follows:

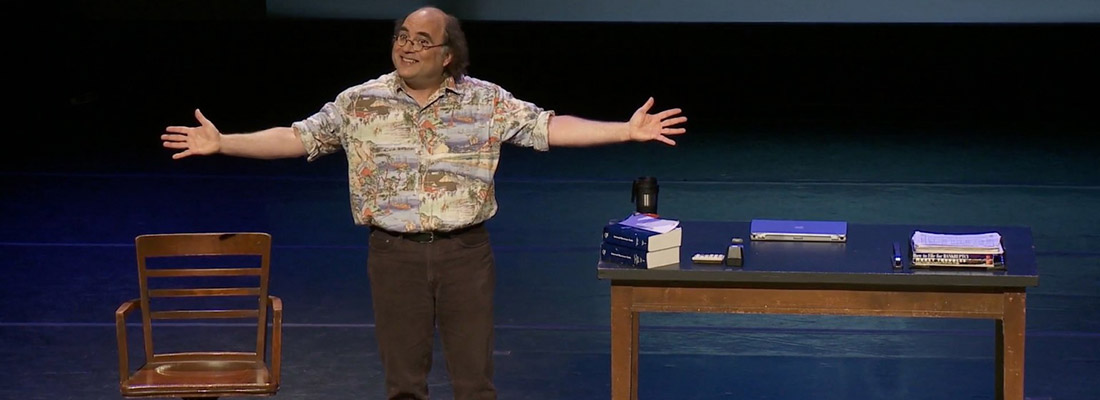

Join monologuist and talk show host Josh Kornbluth for an early improvisation towards his next piece, which may or may not include reflections on philosopher Martin Buber, why Josh can’t drive, and a brief but heartfelt oboe solo.

So I guess that’s what I’ll try to do. I may be entering a phase in my life where I allow my decisions to be made by a higher power. At least, higher powers named Dan.

In preparation (if you can call it that) for this improv, I am reading (or at least starting to read) Martin Buber’s I and Thou. At this point I’m still in the long — and, I must say, thrilling — introduction by the book’s translator, Walter Kaufmann. This intro is one of those pieces of writing in which every sentence has been pared down to what feels like an essential thought. Which can be exhausting: you almost hope for a flabby paragraph or two, just to ease the delicious burden of having one’s mind continually blown — but to no avail.

A bonus, for me: I’m alternating my Buber reading with the pursuit of my first-ever job as a screenplay-doctor. This task terrifies me, as all writing does — but making it worse is that I’m not writing about me, in my voice! Which has been my specialty. And even for this task (okay, not script-doctoring but translating — still, it’s close), Kaufmann has a wise passage:

As a translator I have no right to use the text confronting me as an object with which I may take liberties. It is not there for me to play with or manipulate. I am not to use it as a point of departure, or anything else. It is the voice of a person that needs me. I am there to help him speak.

Okay, Walter — noted. I’ll try. In the meantime, though, I’m going to finish your introduction (so I can get to the actual Buber stuff), then grab a DMV booklet from the library and go home and practice my oboe so I can maybe work in all the things Dan so cavalierly thought up for me to improvise on.

Perhaps from Buber I will learn the answer to that great theological question: Is there someone up there even bigger than Dan?