A few days ago I had my bar mitzvah ceremony on a kibbutz in the Negev Desert. My wife and son and I gathered with Rabbi Menachem Creditor, his daughter Ariel, our guide Jared, and other members of our group at the top of a colorfully painted water tower. As the sun set and a nearby peacock occasionally cried out (quite possibly critiquing me as a naive peacenik), Rabbi Creditor led us in prayer and song, and — as is the tradition — I read my drasha, a personal interpretation of and response to the Torah parsha I’d been assigned: The Book of Numbers, Chapter 25, verses 5-9.

Rabbi Creditor had asked me to include three things in my drasha:

- The story.

- What I thought this text might mean “without me.”

- What I thought this text might mean “through me.”

In the near future (perhaps on the plane, if we have wi-fi), I plan to blog in more detail about that wonderful day and many others that we have experienced here in Israel. But as we prepare to gather as a group for the last time, at our lovely hotel in Jerusalem, I thought I‘d share my little drasha with you.

* * *

Numbers 25: 5-9

And Moses said to the judges of Israel, “Each of you kill his men who cling to Baal Peor.” And look, a man of the Israelites came and brought forth to his kinsmen the Midianite woman before the eyes of the whole community of Israelites as they were weeping at the entrance to the Tent of Meeting. And Pinchas son of Eleazar son of Aaron the priest saw, and he rose from the midst of the community and took a spear in his hand. And he came after the man of Israel into the alcove and stabbed the two of them, the man of Israel and the woman, in her alcove, and the scourge was held back from the Israelites. [Translation by Robert Alter.]

The story:

The Israelites, having escaped their bondage in Egypt, have been wandering in the desert for years and years — and they’re doing a lot of kvetching. Moses had told them he would lead them to the Promised Land, and they had expected this to happen pretty quickly. But then God got angry at their imperfections, and so he made them get lost, and he kept them lost — for a very, very long time. Meanwhile, there are other cults around, like the followers of Baal Peor — who keep sending their women to seduce the Jewish men — and quite understandably many of the Israelites have become Baal-Peor-curious.

Now as the Israelites have been wandering, it is not only they who have been kvetching — God himself has been getting quite testy. He freed the Jews from slavery, and all he asks of them in return is their complete and utter devotion to him and to his many, many, many laws. Every once in a while God decides that he’s had it with the Israelites and has a good mind just to kill them all and start again; each time, Moses talks God down, so that God just kills some of them.

So by the time we get to Chapter 25 of the Book of Numbers, everyone — including God and Moses — is tired and grouchy. And God tells Moses that the Jews had better remain pure — not worshipping pagan gods, and definitely not sleeping with members of other cults, or else God is going to unleash a plague on them. So what happens next? A Jewish guy — a prince, apparently, has sex with a non-Jewish woman (a Midianite) — in the doorway to the Tent of Meeting! Moses, despite what God has told him, does nothing (maybe because Moses’ own wife happens to be a Midianite); and the crowd of Jews just stands there watching as this blasphemous act goes on and on. And then a man emerges from the crowd — Pinchas, son of Eleazar the priest, who is himself the son of Moses’ brother, Aaron — and spears the copulating couple through their genitals, killing them both. And God responds to this act of violent zealotry by weakening the plague, so that “only” 24,000 people die, and rewards Pinchas, and all his descendants, with the covenant of peace.

What would this text mean without me?

The Jewish race, a people chosen by God for a vital, sacred task, must remain pure and completely pious. God tested these people by making them wander in the desert for 40 years, during which many of them felt nostalgic for the lives they had led in Egypt, even as slaves. They stopped following God’s rules, and they questioned whether it was so great to be a Jew, especially given how much they had been made to suffer when they’d followed God’s instructions. The cohesion of their community was in grave danger of eroding; they were eyeing other cults, whose laws — and gods — seemed less stringent. The Jewish man having sex with the Midianite woman seems to be a way of viscerally representing this danger of the Jews’ commingling with non-Jews. Pinchas’s violent act — which may or may not be partly motivated by the fact that Pinchas’s own mother was not Jewish — propitiates God in his fury: Because Pinchas has taken God’s instructions seriously, and literally, God eases up on the Jews, and God elevates Pinchas and all his descendants to an honored status. We should all be like Pinchas.

What would this text mean through me?

God forbid that we should all be like Pinchas! Pinchas commits a reprehensible act of horrific violence against a couple … why? Because God told him to? Because a Jew was sleeping with a non-Jew? I understand, somewhat, how in the context of explaining and promoting the remarkable continuity of the Jewish culture, this might serve as a cautionary tale about the challenges of sticking together in hard times (and a warning that those who don’t stick together will be stuck together). And I realize that many things are different for me, an American Jew living in the 21st century, than for the Jews of Biblical times. I also have an intrinsic respect for the beauty and intricacy of much of Jewish law; to be honest, I am humbled by the rigorousness with which my friends of many faiths try so hard to adhere to their laws and customs. And I am proud to be a Jew.

But Pinchas was a zealot — and people, in his time and mine, who hate and even kill people because God told them to, are my enemies. As human beings, we inherit from nature a capacity both for great creation and for great destruction. Let me admit that I frequently feel both impulses inside myself. It is my hope that at as a species we keep moving, somehow, towards the more loving aspect of ourselves. To do this I believe that we need to have rules to help us live together more ethically, which is incredibly difficult considering the often ferocious impulses of our individual selves, as well as of our families and tribes. But my learning with Rabbi Creditor and other members of my community has convinced me that laws — Jewish and otherwise — must be organic, must be tested and re-tested by each generation through our own experience. I believe that to perform any act — particularly one of hatred and violence — simply because God told me to is to abrogate my responsibility as a member of civilization, and as the beneficiary of a Jewish tradition that has already offered me so much wisdom and comfort.

I believe it is my duty as a Jew to engage with this passage in the Torah — that the lesson for me is to resist the Pinchas in myself, and rather to embrace the difficult, messy task of trying to be a good person in the time and places in which I find myself. Surrounded in this holy land by my dear family and beloved friends, I seek the strength to be gentle, the learning that will allow me to continue learning from others, and the faith that a better world may eventually come.

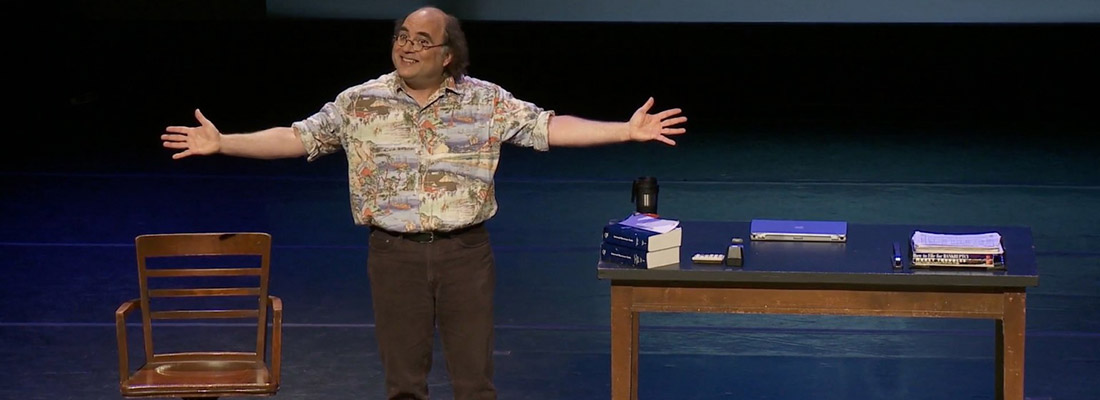

As a man, today, I lay down my spear, reach out my arms to The Other, and say, “Let us live together in harmony and respect.”

I want to respond to the end of your drash: “As a man, today, I lay down my spear, reach out my arms to The Other, and say, ‘Let us live together in harmony and respect.’ ”

I ask: What do you do if The Other responds to you by taking advantage of your open arms and trying to stab you in your vulnerability? I realize this is very different from the situation of Pinchas, but your statement appears to be intended very broadly.

I know, Dan — that’s a crucial question! I don’t mean to suggest that there’s no need for military strength, or for serious negotiation backed by international safeguards — but it seems to me that unless the people who want peace (and I believe that we are the vast majority) reach out to one another, there’s no chance of a nonviolent resolution to our conflicts. However, in all honesty, I don’t yet know enough about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to have a clear formulation, step by step, of what I think should be done. I look forward to learning more, and hope to remain open to discovering the ways that I am wrong.

Thank you for your thoughtful and provocative response!

Welcome home, Josh, and thank you for sharing your experiences with us. I found your dispatches from Israel to be extremely thought-provoking and beautifully written, and hope you will have time to write some more about your adventures after you’ve had a chance to settle in.

Thanks so much, Sue!! I did write one more blog entry about my amazing Israel trip.